The James Oviatt Building: The Bespoke Brilliance and Pretension Behind an Art Deco Masterpiece

JAMES OVIATT BUILDING

October 8, 2017

JAMES OVIATT BUILDING

October 8, 2017

Hadley Meares – September 6, 2013

I have an aversion to — yet a compulsive fascination with — the high end clothing industry. As someone who worked in the luxury concierge business, I spent a portion of my life desperately searching for new ways to write about the finest bespoke suits being crafted on Savile Row. Having seen these suits rumpled and crumpled after long nights out, I realized that a handmade Norton and Sons tuxedo can look remarkably like its Men’s Warehouse counterpart, especially from afar. Up close though, it is impossible not to admire the detailed stitching, that famous “clean line,” and the sumptuous finish of the finest English wool.

That was basically my feeling when I first walked into the Cicada Club in the James Oviatt Building at 617 South Olive Street. It was cavernous and serious, humming with the quiet work of caterers setting up for an evening wedding. The wood mouldings were darkly oppressive, but after I adjusted to the grand ocean liner feel of the place, I found enormous delight in the opulent details. The ornate chandelier gleamed, and the decorative columns were delicately carved — some with crests labeled “service,” others with stylized angels carrying a mission bell to signify “the city of angels.” Then there was the exquisite glass work, done by the master Art Deco craftsman, Rene Lalique. Beautiful panels with stylized ornamentation, reminiscent of Miro, or Picasso’s cubist collages, fractured and softened the light on the second floor. Even the elevator door featured Lalique glass carved with foliage and fruit.

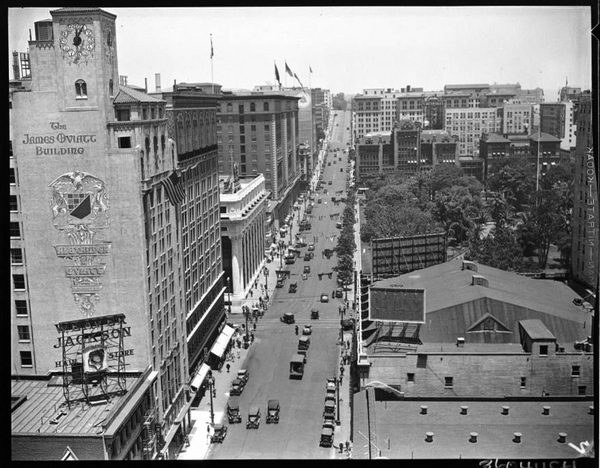

As I stepped outside, I took another look at the diminutive skyscraper I had rushed into earlier. I noticed the whimsical metal work, the Romanesque arches and moulding. I looked up at the building, now dwarfed by surrounding structures, and saw the lovely three-faced clock tower. I knew that right under that tower, in his “castle in the air” penthouse, a man named James Oviatt had lived a good portion of his life.1 He had built Alexander and Oviatt (later known as Oviatt’s), L.A.’s finest haberdashery, from the ground up, and built this building to house the store, using the same exacting detail he used when selecting fabrics. Born into humble circumstances, he had ascended to the heights of his time, always dreaming of the best, until his vision of the world consumed him and limited his views of all that was possible.

James Zera Oviatt was born in 1888 in Farmington, Utah. His father was a blacksmith, but Oviatt preferred to emphasize the fact that his mother was French and his father English, therefore imparting him with impeccable taste. After working in Salt Lake City, he came to Los Angeles in 1906 and was employed as a window dresser at Desmond’s Department Store. Quickly rising through the ranks, Oviatt, and a hat salesman named Frank Alexander, decided to start their own luxury men’s shop. Their motto was “the best is none too good.”2 Oviatt explained:

Even back in 1911, when we opened a little shop at 209 West Fourth Street and placed above the door the firm name Alexander and Oviatt we dreamed, even at that early date, of greater things for the future.3

His dreams were steadily realized. The store was a success, filling a void in the Los Angeles market. L.A.’s forming society and the burgeoning film colony were desperate for all the trappings of the Eastern and European elite. Alexander and Oviatt provided the tangible accoutrements and clubby atmosphere that these self-made men, embarrassed by their past, needed to feel that they had arrived. In 1914 the firm moved to spacious quarters at Sixth and Hill. Frank Alexander’s death in 1921 did not slow the business down, and in 1923 the store expanded into women’s wear.

The roaring ’20s were tailor made for the Oviatt brand. It was an era of conspicuous consumption, and nothing said “moneyed” like a perfectly crafted cravat. Oviatt became a celebrity in his own right. Professionally imperious, he worshiped Abe Lincoln because “he solved his problems alone.”4 He terrified employees with his frequent store inspections, checking for dust on countertops with a swipe of his perfect, fitted white glove. For all his pretensions, the suave Oviatt was privately a great deal of fun, and a very popular and sought after social guest. He was also an avid golfer and a member of the Los Angeles Athletic Club, where his stash of rare brandies and scotch whiskies was discovered in a locker during the height of prohibition.

Oviatt’s yearly, three month-long buying tours of European fashion capitals were considered citywide news. At a time when trans-continental travel was rare, he was expected to bring back gossip and political observations. In 1920 he reported that prices in England were skyrocketing due to “labor getting its just dues.”5 By his 1925 trip he had become fed up with the English, stating: “The English laboring man seems to think that it is better to get two pounds a week from the government than it is to work and make twice that.”6 Three years later he was singing Germany’s praises, impressed with their quality of workmanship and their post war financial advances.

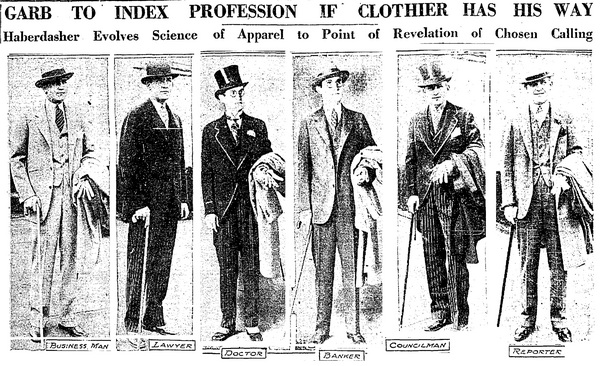

He also seems to have had a sense of humor about his haughty profession. In an amazing 1927 spread in the Los Angeles Times, he revealed his choice of uniform for various male professionals, firmly believing that every profession called for a definite (and elaborate) style of attire. City councilmen were to wear:

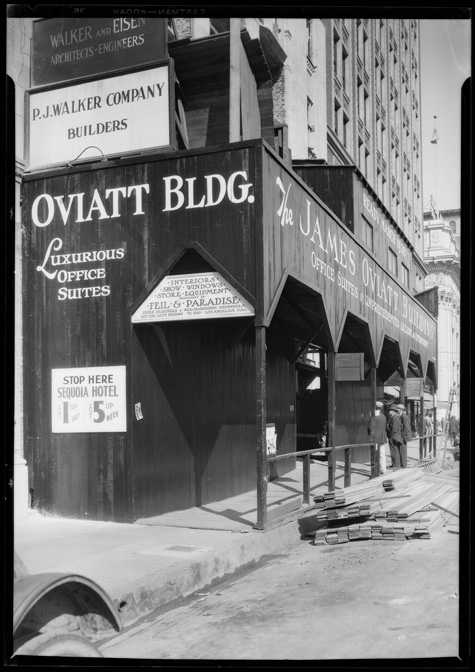

In 1927 construction began on the building at 617 Olive Street. This was already the hippest neighborhood of downtown Los Angeles, featuring The Biltmore Hotel, the Athletic Club, and the Pacific Finance Building. Buildings were capped at a height limit of 12 stories, and in 1926 twenty-three of these early skyscrapers were built. The following year promised the construction of even more, including Oviatt’s thoroughly modern Romanesque-Art Deco hybrid. Alexander and Oviatt would occupy the first three floors of the building and the basement, while the rest would be rented out to suitable businesses.

Oviatt had fallen in love with Lalique glass at the famous 1925 Exposition in Paris. Soon, thirty tons of custom-made Lalique, including a ceiling, doors, chandeliers, and elevator panels were shipped through the Panama Canal, the largest shipment of its kind to America. Draperies, rugs, and tons of French grey marble “tinged with brown and crimson” were also imported. Mailbox and lighting fixtures were made of a new white metal known as “melchior,” and even the toilet bowls were to be a rich tan to complement the dark wood work. Bronze statues were posted prominently throughout the store, and the “Outdoor California Palm Grove” was constructed so men could see their new clothing in natural light.

When the building and the new store, designed by the firm of Walker and Eisen, was opened on May 15, 1928, the city was in awe. Reporter Olive Gray rhapsodically riffed on the building that Oviatt had “dreamed true,”8 writing:

But nothing matched the grandeur of Oviatt’s personal “castle in the air,” which he moved into two years later. This grand, ten room penthouse boasted a Turkish bath, a gym, a tennis court, practice golf links, a rooftop garden, and a pool with sand imported from France to make a private beach. The blacksmith’s son was on top of the world.

The James Oviatt Building quickly filled to capacity with lawyers, ad agencies, insurance firms, political campaign offices, and the National Association of Safe Driving Motorists. Disgraced district attorney Asa Keyes had offices there, and his dealings in the Oviatt Building were discussed during his 1928 bribery trial. In 1930 Miss Isabelle M. Hanbury opened her “College of Cultural Subjects.”9 She taught “social success and etiquette, the art of conversation, cultured speech and vocabulary, public speaking, appreciation of literature and history, law for layman, languages, psychology, logic, philosophy and ballroom dancing.”

The Depression decimated the high end clothing business, and an “embarrassed” Oviatt lost his controlling interest in both his store and his building. Speaking to his employees at the height of the crisis, he stressed, “we’ll see it through.” He retained his entire corps of salespeople, even while staging a drastic inventory clearance sale. By April 1933, Oviatt was able to announce that he had paid off all creditors and regained control of the store and his beloved building. That week, the Director of the Chamber of Commerce, Major R.M. MacLennan, during a radio interview, congratulated Oviatt on his resurgence. By June, Oviatt was able to announce a pay raise for all his employees. “It demonstrates not only my faith in the national administration’s activity to create more jobs and higher salaries, but also the fact that tangible business betterment permits such a step. It is a token of my appreciation to the men who have fought with me to victory,” he stated.10

That summer a big party was thrown for Oviatt by his “Divot Club” golfing pals. The party, at the Cocoanut Grove, was to celebrate the reopening of a bigger and better Alexander and Oviatt. He also expanded his brand by opening a store at his friend Walter G. McCarty’s Beverly Wilshire Hotel. His employees were fond of him, and the 40% discount they received on all Oviatt goods.

As Oviatt conquered the Depression, he also continued to conquer Los Angeles high society. The 1930s found Oviatt, the perennial bachelor, at the center of the smart, café society set that flourished in the inter-war period. He was a founding member of the Turf and Jockey Club, and along with such notables as Harold Lloyd, Robert Montgomery, Chico Marx and Lionel Barrymore, pledged to hold “clean racing sponsored by responsible sportsmen.”11 The club’s first headquarters were at the Oviatt Building, before they were moved to the new tracks at Santa Anita. Tickets to the inaugural meet at Santa Anita were sold at Alexander and Oviatt. Of course, Oviatt attended, looking “the perfect sportsman in tweeds.”12

And so it went. The flagship store continued to flourish, and its owner continued to party. One night he would be at the Mayfair Club with Pat O’Brien and Leo McCarey, the next at a “Gay Nineties” theme party with Spencer Tracy and Dolores Del Rio. He won the putting prize at the “Divot Diggers” tournament at the exclusive Hillcrest Club. In 1941 he could be found at a “lake stag party” given by J. Benton “Bent” Van Nuys, where they fished, hiked, and bowled, “showing the younger generation how they used to roll ’em years ago.”

1 “Restaurant Planned for Oviatt” Los Angeles Times, April 8, 1979

2 “Door Open at New Men’s Shop” Los Angeles Times, May 16, 1928

3 “Alexander and Oviatt Goal Won” Los Angeles Times, August 12, 1931

4 Ibid.

5 “Studies Hindenburg Line from the Air” Los Angeles Times, September 9, 1920

6 “Importer Paints Drab Picture of Europe’s Plight” Los Angeles Times, September 14, 1925

7 “Garb to Index Profession if Clothier Has His Way” Los Angeles Times, April 27, 1927

8 “Door Open at New Men’s Shop” Los Angeles Times, May 16, 1928

9 “City Leads in One Form of Teaching College of Cultural Subjects Hires Instructors of Outstanding Ability” Los Angeles Times, August 27, 1933

10 “Salary Raise Announced by Oviatt Word” Los Angeles Times, June 27, 1933

11 “Prominent L.A. Businessmen Luncheon at Biltmore Yesterday” Los Angeles Times, 1933

12 “Racing Tickets Due to Go On Sale Today” Los Angeles Times, December 7, 1934

13 “Spain Leads Europe Say James Oviatt” Los Angeles Times, August 18, 1952

14 “Ex Klan Leader Linked to California Rangers” Los Angeles Times, April 13, 1965

15 “Oviatt Denies He Financed Radical Unit” Los Angeles Times, April 13, 1965

Top: Art deco gate at the Oviatt Building. Photo: ibison4/Flickr/Creative Commons

ABOUT THE AUTHOR – HADLEY MEARES

Hadley Meares is a writer, historian, and singer who traded one Southland (her home state of North Carolina) for another. She is a frequent contributor to Curbed and Atlas Obscura, and leads historical tours all around Los Angeles for Obscura Society LA. Her debut novel, “Absolutely,” is now available on Amazon.